By: Bryan Watts

1/4/2024

We put in on Hoskins Creek in Tappahannock and ran out to the open Rappahannock River. Mitchell Byrd was at the helm of a classic Boston Whaler – a 1970s vintage with an aquamarine deck and a low console that was a little less than waist high. As we came around Jones Point Mitchell opened up the motor and we turned to the southeast toward the mouth of Piscataway Creek. Approaching the creek channel, the boat came to a thumping stop sending me sprawling onto the deck. It was all I could do to stay aboard. When we stopped entirely, I was hanging off the bow looking down at milky sand in a foot of water. Mitchell was draped over the console unable to reach the throttle. When the motor shut off on its own, Mitchell fell back onto the deck between the console and the bench seat moaning from where the throttle had hit him square in the crotch. Finally able to right myself, I walked back to see Mitchell assuming the fetal position. When I asked if I could help him up, he just moaned, “not yet.”

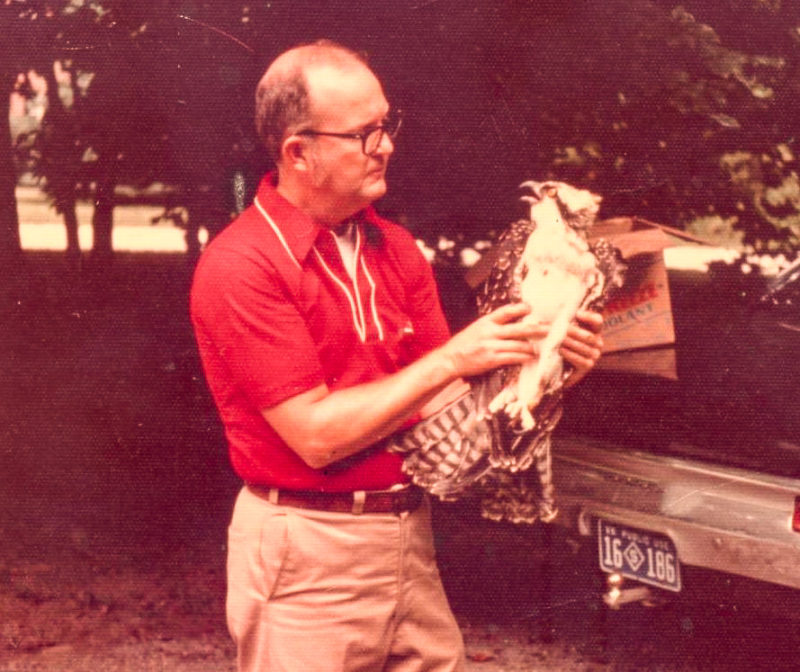

When the captain was able to stand up straight, we poled back off the sandbar and went around to collect two young osprey from different nests. Both osprey were put in pet carriers and stowed. We gave the sandbar a wide berth as we idled out of the creek and then ran back to the boat ramp to load the birds with others. We headed to the airport and waited for a pilot to arrive from Ohio and all birds were loaded for transport. The birds were flown to hack towers on an inland lake. They would be in the hack tower before dark and would be fed for a month until they dispersed on their own. The short excursion out on the Rappahannock was one of many high adventures collecting young osprey for release programs.

During the height of the DDT era, osprey populations within many inland states were lost completely or reduced to less than five pairs. The decline resulted in many states listing osprey as either state threatened or endangered. Several states established dedicated programs to re-establish their populations. Because the Chesapeake Bay population was still large and recovering by the late 1970s, these states looked to the Bay to serve as a donor population for their reintroduction programs.

Between 1980 and 2006, the Chesapeake Bay would provide more than 850 young osprey to reintroduction programs within Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia, Ohio and Indiana. Osprey young were collected from the Patuxent River in Maryland and the Rappahannock River, Piankatank River, York River, Back River and James River in Virginia. Gary Taylor, Bradley Dorf, Steve Dawson, Steve Cardano, Greg Kearns, Mitchell Byrd, Reese Lukei, Bryan Watts and Tom Olexa from Virginia assisted in this process. The Center provided nearly 50% of these birds. Hack towers were established within dozens of freshwater systems within recipient states. Nesting pairs were established in most states within three years of the initial releases. The osprey translocation program has been remarkably successful. Osprey have been declared “recovered” within all states and have been removed from the list of threatened and endangered species. Collectively, the breeding population for these states is now more than 750 breeding pairs. Within just a single generation, the public is now able to enjoy nesting osprey on many bodies of water within every state.